Working with clients around medical compliance and adherence to the lifestyle prescription is the place where Prochaska's "Readiness for Change", Elizabeth Kubler-Ross's "Stages of Grief ", and Maslow's "Hierarchy of Needs" all intersect. What we, the caregivers often fail to understand is that when a person has experienced a truly life changing event, like the onset or worsening of a health challenge they feel a loss of control that may threaten their safety, they experience grief at the loss of health, ability, or dreams, and often need to redefine their identity.

Working with clients around medical compliance and adherence to the lifestyle prescription is the place where Prochaska's "Readiness for Change", Elizabeth Kubler-Ross's "Stages of Grief ", and Maslow's "Hierarchy of Needs" all intersect. What we, the caregivers often fail to understand is that when a person has experienced a truly life changing event, like the onset or worsening of a health challenge they feel a loss of control that may threaten their safety, they experience grief at the loss of health, ability, or dreams, and often need to redefine their identity.

As wellness and health coaches are given more opportunities to help people, especially people  who have, or may soon develop, a chronic illness (heart disease, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, COPD, etc.), we will face again and again what has stymied healthcare professionals for decades; the patient who has heard the diagnosis, but has made virtually no changes to improve their health. They have gotten the news, but haven't woken up and smelled the coffee. The story is far too familiar. You may have seen it amongst the people you work with, your friends or in your own family. It may have been what you have experienced yourself. The person gets a new diagnosis of a life-threatening disease, or is warned that a life-threatening disease is immanent (such as being told that one is pre-diabetic) unless they make significant lifestyle changes. Or, perhaps they experience a sudden health event like a heart attack. They are given medical treatment and also given the "lifestyle prescription". They are told to make lifestyle changes: quit smoking; be more active and less sedentary; improve their diet; manage their stress better, etc. They may even be told that immediate lifestyle changes are absolutely essential to their continued survival: a low-sodium diet for the hypertensive patient; lower stress levels for the post-heart attack patient; complete restructuring of the diet of the newly diagnosed diabetes patient, etc. Then, far too often, the healthcare professional watches, as do family and friends, in total astonishment, as the patient makes none of these changes. So, when lifestyle changes are necessary what determines a person's ability to make the needed changes in the quickest way possible?

who have, or may soon develop, a chronic illness (heart disease, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, COPD, etc.), we will face again and again what has stymied healthcare professionals for decades; the patient who has heard the diagnosis, but has made virtually no changes to improve their health. They have gotten the news, but haven't woken up and smelled the coffee. The story is far too familiar. You may have seen it amongst the people you work with, your friends or in your own family. It may have been what you have experienced yourself. The person gets a new diagnosis of a life-threatening disease, or is warned that a life-threatening disease is immanent (such as being told that one is pre-diabetic) unless they make significant lifestyle changes. Or, perhaps they experience a sudden health event like a heart attack. They are given medical treatment and also given the "lifestyle prescription". They are told to make lifestyle changes: quit smoking; be more active and less sedentary; improve their diet; manage their stress better, etc. They may even be told that immediate lifestyle changes are absolutely essential to their continued survival: a low-sodium diet for the hypertensive patient; lower stress levels for the post-heart attack patient; complete restructuring of the diet of the newly diagnosed diabetes patient, etc. Then, far too often, the healthcare professional watches, as do family and friends, in total astonishment, as the patient makes none of these changes. So, when lifestyle changes are necessary what determines a person's ability to make the needed changes in the quickest way possible? We have long tried to understand people's adherence to recommendations for lifestyle improvement through the lense of Prochaska's Readiness For Change model (Changing For Good, Prochaska, et.al. 1994). This model, though primarily tested with addiction clients, revolutionized how we think about behavioral change in the healthcare world. James Prochaska and his colleagues reminded us that change is a process, not an event and that people change when they are ready to, not before. Furthermore the change process is made up of six stages, not just ready or not-ready.

We have long tried to understand people's adherence to recommendations for lifestyle improvement through the lense of Prochaska's Readiness For Change model (Changing For Good, Prochaska, et.al. 1994). This model, though primarily tested with addiction clients, revolutionized how we think about behavioral change in the healthcare world. James Prochaska and his colleagues reminded us that change is a process, not an event and that people change when they are ready to, not before. Furthermore the change process is made up of six stages, not just ready or not-ready.

Pre-contemplation → Contemplation → Preparation → Action → Maintenance → Termination (Adoption)

This is certainly a helpful way to understand where someone is at regarding a particular behavioral change. Knowing if they are in the Contemplation or Preparation stage, for example, helps us know how to work with them. This single lens, however, is not enough. In the patient/client who astounds us with their level of non-adherence we find we are encountering more than just lower levels of readiness, we are encountering grief and loss.

A loss is a loss. The loss of a loved one through death, the loss of one's health, or the loss of the dream held for how life would be, is all perceived as losses to be grieved. To help you understand a person's reaction to a health challenge, diagnosis, etc., and to help you respond more compassionately and effectively, put all of it in the perspective of the classic stages of grief. The work of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, Stephen Levine and others have shown us that the grieving process is a multi-layered experience that affects us powerfully. Kubler-Ross identified the five stages of grieving that are present for any significant loss: 1) Denial; 2) Anger; 3) Bargaining; 4) Depression; and 5) Acceptance. I talk about this extensively in chapter ten ("Health and Medical Coaching- Coaching People With Health Challenges") of my book, Wellness Coaching For Lasting Lifestyle Change, 2nd Ed., 2009. When we see the astonishingly non-compliant patient/client, they are often experiencing this first stage of denial. They minimize the importance of the event, downplay its seriousness, and do all they can to return to "business as usual". Talking about the event or diagnosis becomes a forbidden subject and the person may become quite defensive.

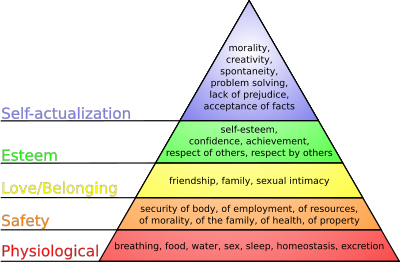

The experie nce of a "brush with death", or even the news that such a threat is imminent, can automatically push us into survival mode. No matter at what level we were getting our needs met on Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs (see Chapter One - "Toward A Psychology of Wellness" in my book, Wellness Coaching For Lasting Lifestyle Change, 2nd Ed. 2009) such an experience necessarily drives us down to the survival need level. We feel profound threat to our "safety needs" and "physiological needs", our very physical existence is threatened. Life becomes about the real basics of survival; the next breath, food, water, shelter. It becomes about the basics of safety; feeling secure, going back to the familiar, whatever reassures us that we will be OK. It is no wonder that people going through such an experience may embrace the status quo, resist change and psychologically minimize the threat that they perceive.

nce of a "brush with death", or even the news that such a threat is imminent, can automatically push us into survival mode. No matter at what level we were getting our needs met on Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs (see Chapter One - "Toward A Psychology of Wellness" in my book, Wellness Coaching For Lasting Lifestyle Change, 2nd Ed. 2009) such an experience necessarily drives us down to the survival need level. We feel profound threat to our "safety needs" and "physiological needs", our very physical existence is threatened. Life becomes about the real basics of survival; the next breath, food, water, shelter. It becomes about the basics of safety; feeling secure, going back to the familiar, whatever reassures us that we will be OK. It is no wonder that people going through such an experience may embrace the status quo, resist change and psychologically minimize the threat that they perceive.

This brings up questions about the health challenged persons readiness to change:

- How long will they stay at these survival levels seeking to meet their physiological and safety needs when they are encumbered by the initial stages of grief?

- How effective can one be at functioning and rising up through both the stages of readiness for change and the lower levels of the needs on Maslow's model if they are in denial and minimizing, acting out in an angry manner or shackled by depression?

What needs to be considered to work effectively with health challenged clients is the intersection of these three widely accepted psychological theories. Once understood, a Wellness Professional can truly motivate their client towards lasting lifestyle change.

Maslow's theory of motivation contends that as people get their needs met at the lower levels of the Hierarchy of Needs Triangle (their  deficiency needs), they naturally move on up to the higher levels (their being needs). When we encounter a patient/client who fits the picture we are talking about here, do we acknowledge where they are at and do we help them get their needs met at that level? Or, do we demand immediate behavioral change just because the value and urgency of it is so great?

deficiency needs), they naturally move on up to the higher levels (their being needs). When we encounter a patient/client who fits the picture we are talking about here, do we acknowledge where they are at and do we help them get their needs met at that level? Or, do we demand immediate behavioral change just because the value and urgency of it is so great?

Our first job is help them feel like they have an ally, someone who supports them and has their best interests at heart. This helps meet their safety needs and even some of their social needs. We then need to check in with the person and see how they are doing at the survival level. Are they receiving the medical care they need? Is their living situation allowing them to cover the basics of shelter, food, and safety? Much of this comes down to how their health challenge affects the security of their way of making a living. How do they perceive (and it is their perception that counts) their health challenge as a threat to their livelihood? Do they fear losing their job, falling behind in production, having their business falter or fail? How much are they into catastrophic thinking about all of this?

What is more frightening than to believe we are powerless? The threat to our very survival is there, like a cave bear at the mouth of our cave, and we believe we can do nothing to stop it. If our patient/client feels powerless to affect the course of their illness then they wonder why should they make all the effort required to achieve lifestyle improvements? When we feel powerless we often don't go to fight or flight, we freeze.

The reflexive response to fear is contraction. Hear a sudden, loud noise and we instantly tense up and contract all our major muscle groups. When we are scared, we hold on. We reflexively hold on to what we have and to the way things are. Change seems even scarier than what frightened us to begin with. We are like the person in the path of a hurricane who won't leave the safety of home, sweet home, even though it will probably be flooded and blown away.

For our client to "let go" and trust in the change process their physiological and safety needs have to be met. If they doubt this they may give the appearance of compliance, but their follow-through is questionable.

Beyond the very basics of survival, we can help our client then to get their needs in the next two levels met: Social Needs (sense of belonging, love) and Self-esteem Needs (self-esteem, self-worth, recognition, status). This is where coaching for connectedness plays a priceless role. We know that isolation is a real health risk and at this crucial time the presence and engagement of an extended support system can provide huge benefits. Our client will need the help of others in many practical ways, but they will fare far better if they are getting the emotional support that comes with getting their needs for belongingness, acceptance and compassion met. We, the helper can only provide a very small part of this and some of our best efforts may be to help the person we are working with to find, develop and expand sources of support in their lives. The nature of the support they receive from others is important as well. This person needs understanding, empathy and support, not criticism and pressure to make lots of changes immediately. We need to encourage our client to ask for the support they need in the ways that they need to receive it.

Coaching to improve self-esteem allows the client to move on up through Maslow's triangle through the next level. We all need to feel good about ourselves, to receive recognition and praise. When one is hit with a health challenge they may feel anything but good about themselves. Perhaps they are framing the health event or onset of an illness as a personal failing. There may be embarrassment and/or shame that they are no longer completely healthy. Their own "inner-critic" may be very harsh on them, filling their mind with self-critical thoughts that, again, cause them to do anything but take action for change. Helping the person to regain a sense of power and control in their life can also reclaim self-esteem. When we feel powerless to control events and circumstances in our lives we feel weak, vulnerable and impotent. When we discover what we can actually do through our own lifestyle choices to affect the course of our illness for the better, we feel empowered and regain confidence and strength.

Ten Ways to Effectively Coach the Health Challenged

When we encounter: the person who has had a heart attack and is still downplaying the importance of it, almost pretending that it didn't happen; the person diagnosed as pre-diabetic who has made no dietary changes at all and remains as sedentary as ever; the person diagnosed with COPD who is still smoking, etc., we need to respond to them in a more coach-like way. In each step consider that their readiness for change will be determined in part by their stage of grief and where they fall in Maslow's hierarchy of needs. How quickly they move through the change process will be in part determined by past experiences and in part by the support they have in the present to change.

1) Meet them with compassion not judgment.

Catch yourself quickly before you criticize their lack of adherence to the recommended lifestyle changes they have been told to do. Bite your tongue, so to speak, and instead of forcefully telling them what they should be doing, and warning them, once again, of the dire consequences of non-adherence, respond with sincere empathy and listen.

2) Acknowledge and explore their experience.

Ask them what it was like when they found out about their health challenge; diagnosis, or what is was like when they experienced this health event. Don't jump to solutions or start problem solving. Just listen and really listen. Reflect their feelings. Acknowledge what was real for them. Explore it with them and see if there isn't some fear that needs to be talked about here.

3) Don't push, stay neutral in your own agenda, and explore more.

While it may feel like this person needs to take swift action with tremendous urgency, be patient. Readiness for change grows at a different rate for each step of the journey.

4) Be their ally.

Help them feel that they are not facing this alone. This helps meet their need for safety and even some of their social needs. Does the client understand their health challenge? To what degree does the client understand and buy into the lifestyle changes suggested?

5) Address survival first.

Make sure they are getting all the medical help they need. Explore their fears about income, job, career, business, and how it all will be impacted by their health challenge. Help them gain a sense of control and feel more safe and secure in all ways. Help them to see that they are not completely helpless and vulnerable, but that there are ways they can affect their situation.

6) Help them process the loss.

Talking through the grief is very powerful. The loss of health is felt to the level that it is perceived. That perception will be part reality and part fear. Help your patient/client to process their feelings, to give a voice to the part of them that is afraid. Accept their initial tendency to minimize but slowly help them feel safe enough to move through the other stages of grief (anger, bargaining, depression and finally, acceptance).

7) Help them form a plan.

Even if it is very basic, help them develop a plan for becoming healthy and well again and how to face their health challenge. Meet them where they are currently remembering that Preparing to take action is a vital readiness for change stage. What do they need to know? Having a plan will give them both hope and a sense of purpose and direction, a map to find their way out of their current situation. It is something to hold on to.

8) Coach for connectedness.

If the basic survival needs feel met the person can reach out to others and will benefit from a sense of belonging. Family and friends need to be inclusive and not critical. Support from co-workers is also extremely helpful. The fear that is brought up by the onset of serious health problems sometimes frightens others and efforts need to be made to break through this initial resistance. Coach them through their own reluctance to asking for support.

9) Build self-esteem.

Recognize, acknowledge and reinforce all progress. There is no wrong! Help your patient/client to exhibit greater self-efficacy because as they take charge of their health and their life, their self-esteem grows.

10) Nothing succeeds like success.

Help the health-challenged person to take small steps to prepare for change and then experiment with actions where they are most ready. Build on these easier successes and leave the tougher challenges for later after confidence has been built.

Maslow reminds us that "growth forward customarily takes place in little steps, and each step forward is made possible by the feeling of being safe, of operating out into the unknown from a safe home port, of daring because retreat is possible." (Toward A Psychology of Being, 1962). To emerge from that home port, our client needs to be in the process of working through their grief, they need to be moving up the spiraling stages of change, and how better to set sail towards the unknown lands of change than with a good ally?

Michael Arloski, Ph.D., PCC